Then, twenty years later, in 1975, Lindgren decided to do it over again and produced The Brothers Lionheart.

It was heartbreaking, for me, though Eila didn’t notice she was still caught up in the real story, which is excellent though also a wee bit sappy and the-stars-are-god’s-daisy-chain-ish. Karl Anders Nilsson is in Farawayland with his father the King, and all is well with Mio.” He’s in a place where the silver poplars rustle… where the fires glow warm at night… where there is Bread that Satisfies Hunger… and where he has his father the King who loves him and whom he loves. But Aunt Hulda is wrong! She’s absolutely wrong! There’s no Andy on any seat in the park. And I suppose she’s cross because I’m so long coming home with those buns. “Perhaps that’s where thinks I am, watching the houses where there are lights in the windows and children are having supper with their mummies and daddies. But it’s not until the final paragraph that we know for certain that the boy has been sitting the whole time on a bench in the park, unwilling to go home to his truly awful life.

Except that we don’t actually find out until the last page. This is what Lindgren does in Mio My Son. The other is to tell a story in which the hero has the fantasy. One is to tell a story in which the hero leaves home and finds his real family, or his proper place in the world – a buildungsroman would be a loose example of a family romance especially if, as in Oliver Twist and many other novels, the hero does eventually find a rich relative. Apparently lots of children fantasize along these lines from time to time, but there are two ways to put it into a story. It involves what Freudians call a “family romance,” which means a child’s fantasy that his parents are imposters and that he has real (and likely royal) parents elsewhere, who will eventually come for him.

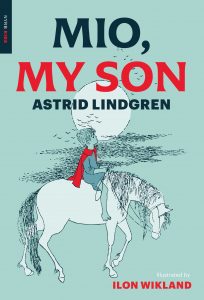

Of all the chapter books we read this summer, the strangest two were by Astrid Lindgren.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)